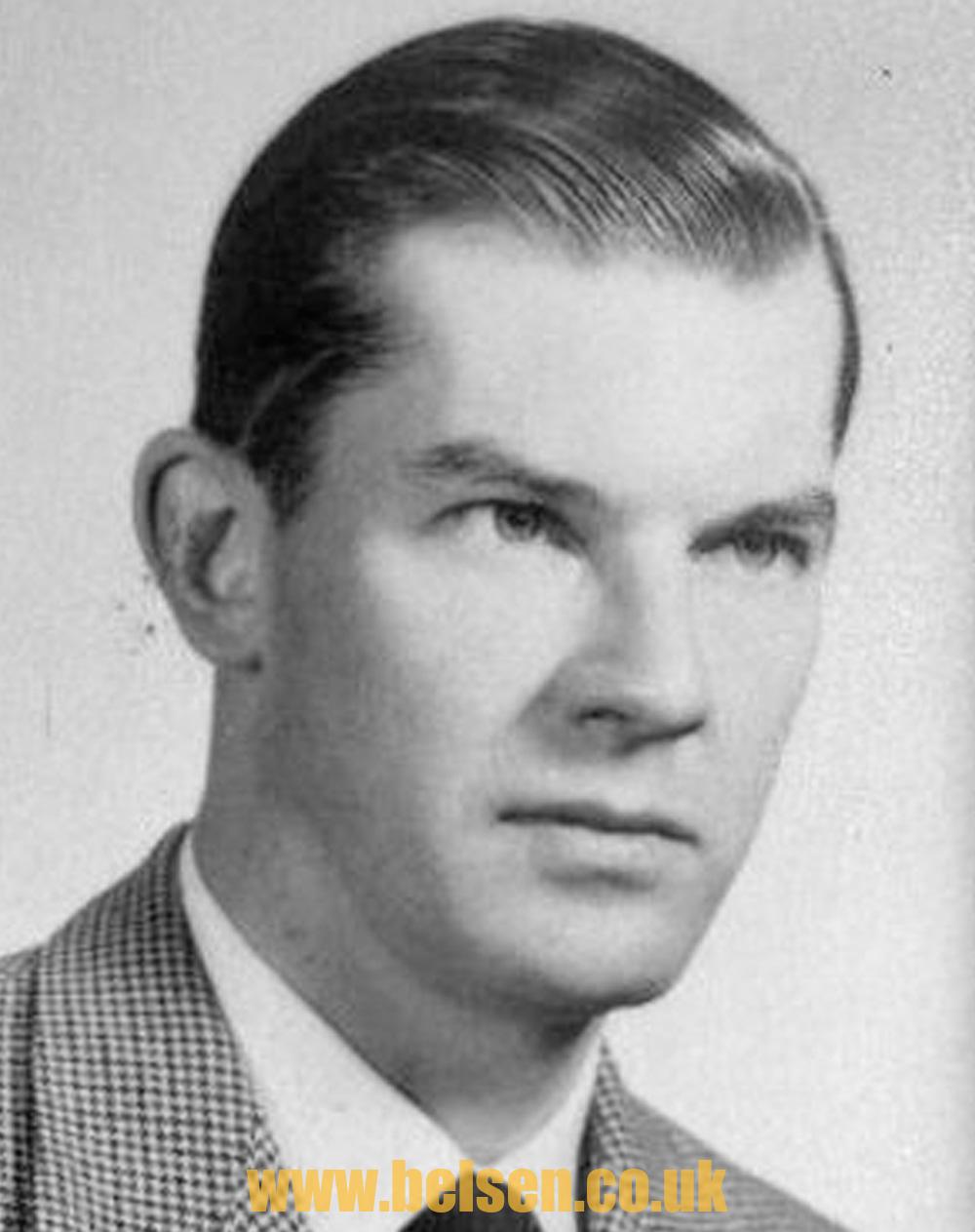

Thomas Gibson – Medical Student

During early April a notice appeared in the Medical Schools of the London hospitals asking for twelve volunteers from each to make up a party of a hundred students, whose object would be to treat starvation cases in Holland under the auspices of the Red Cross.

The students chosen waited for the imminent liberation of the Dutch people. This proved slow, so we resigned ourselves to a period of inactivity. In the meantime we were inoculated against a variety of diseases, with a variety of immediate results.

The students chosen waited for the imminent liberation of the Dutch people. This proved slow, so we resigned ourselves to a period of inactivity. In the meantime we were inoculated against a variety of diseases, with a variety of immediate results.

On 28 April we assembled at the British Red Cross headquarters, where we joined a motley crowd of ‘civilians in uniform’. We were issued with passports and important looking papers, which we were told never to be without unless we wished to be shot as spies. At that time it would have needed more than papers to convince anyone that we had any legitimate reasons for being in Europe. Then it was mentioned, in as kindly a fashion as possible, that our destination was Belsen. Everyone realised the seriousness and the import of our task ahead.

We entrained for Cirencester, where we were greeted by a solitary porter. We arrived at staging camp in a blizzard, the darkest night of the year, and complete confusion. Eventually the scene became less Dantesque and everyone was sorted out. A meal of baked beans, spam and hot tea was provided. We were told that reveille was to be at 4.30 am as the planes had to leave by 6 am. And so to bed.

A minute later an impolite soldier stormed the hut, inviting us into the cool morning air in no uncertain fashion. After a breakfast of baked beans, spam and hot tea we were taken to Down Ampney aerodrome. In the freezing cold we climbed into Dakotas. A few hours later we climbed out again, for flying had been cancelled owing to icing conditions, and we returned to camp. For the next three days our routine was the same, our meals were the same, our disappointments were the same, till we despaired of ever getting out of England.

But on 2 May we took off for an uneventful journey. Signs of allied bombing on a large scale were obvious, and for many miles on both sides of the Rhine the fields were pitted with shell-holes. Eventually after four hours’ flying we landed at Celle, which had been in German hands until three weeks previously and which was now a busy transport-cum fighter aerodrome. Lorries then took us to the Panzer training school barracks, our future quarters; these barracks were extraordinarily good, and it would appear that the German soldier was well looked after. A former officers’ mess was placed at our disposal. Some English sporting prints hung on the walls, no doubt to indicate to the Herrenvolk that they were only fighting fox-hunting gentry, who, one must confess, looked singularly asinine in these prints.

After a night occasionally disturbed by a fusillade of shots, we went down to Camp 1, the concentration camp proper, about a mile away. Belsen was a comparatively old camp and off the beaten track. Conditions there had been relatively reasonable until February, when the camp rapidly became the terrible cesspit that it was when the British liberated it on 17 April. The two main factors which contributed to this were over-crowding, due to the arrival of many internees from camps such as Auschwitz that were about to be overrun by the Russian armies, and a typhus epidemic due to the non-segregation of a group of Hungarians who had been in cattlecars for ten days. Naturally, conditions were perfect for the spread of any disease, due to lack of sanitation and to crowded conditions.

Shortly after the first British troops had entered the camp a party of Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) officers had made a tour of the whole area, and the Senior Medical Officer had written the following account:

“Camp I consists of huts housing 22,000 females and 18,000 males.

Camp II, of brick buildings, 27,000 males. All European nationalities are to be found, but chiefly Russians, Czechs, Belgians, French and Italians.

Conditions prevailing. It is impossible to give an adequate description of the camp when entered on April 17th 1945. Camp I was full of emaciated and apathetic scarecrows – without beds or blankets and some completely naked. The females are worse than the males and most have only filthy rags. The dead are lying all over the camp and in piles outside those blocks, miscalled hospitals, housing the worst of the sick. There are approximately 3,000 corpses in varying stages of decomposition. There is no sanitation, but there are pits, some with birch rails. From apathy, or weakness, most defecate in the huts or anywhere. No running water, no electricity, and all water brought by water-trucks. Death rate is not known. Camp II is better, but there are 600 housed in buildings of 150 capacity. These internees are better clad and less emaciated, and attempts are made to bury the dead.

Diseases prevalent Camp I – Riddled with typhus and TB. Gastroenteritis common. No cholera or dysentery diagnosed. Erysipelas and scurvy are prevalent. Camp II – Enteric, TB, Erysipelas. No typhus.

Rates of Sickness Seriously ill requiring hospitalization, but excluding starvation cases and those who will inevitably die:

Camp I – Males 900, females 2,600.

Camp II – Males 500. Total, 4,000.Medical personnel – Internees fit to work

Camp I – Doctors 42, Nurses 33.

Camp II – Doctors 7, Nurses 50.Medical stores – Negligible.

Urgent Measures to be taken

- (a) Bury dead.

- (b) Evacuate patients in Camp I to suitable clean buildings in Camp II, with plans for reception, delousing and cleaning.

- (c) Evacuate fit from Camp I to Camp II

- (d) DDT all inmates.

- (e) Arrange suitable feeding for patients. Death rate has increased since abundant food became available.

- (f) Pile and burn masses of rubbish, rags and human excreta which litter the camp.

Work has started on all these projects, and in addition a hospital area in Camp II has been earmarked and is being evacuated and cleaned prior to the reception of seriously ill patients from Camp I. This is to be for 7,000 patients, and the following are urgent minimal requirements: blankets 14,000, stretchers 5,000, palliasses 7,000, bed-pans and equivalent 700, urinals 700, cooking utensils for 7,000.”

The situation was therefore grave, and as the fighting had not yet ended the number of available RAMC units was few. In spite of this, miracles were performed by the RAMC and the Royal Artillery troops. The inhabitants of the hundred huts in Camp I were not supervised medically or dietetically and were dying at the rate of 500 per day. So when we came into the camp on 3 May our primary objective was to supervise the huts, working in pairs. The conditions in these huts were never to be forgotten. We who were there cannot allow such appalling inhumanity of man to man to be erased from the conscience of all people, either because they do not believe or do not wish to believe. We saw it, and it was worse then we could possibly have imagined in our wildest dreams.

Medically, there was little we could do during the first fortnight, because the few drugs available were in limited supply. Diagnosis and treatment were empirical and nursing help was non-existent. To explain to a Pole who speaks a little French how to give a course of sulphonamide to a Russian with erysipelas who only speaks Russian is no easy matter, and we had no means of ensuring the course was correctly given. We usually managed to give a pill of sorts to all, which, although useless in itself, was of great psychological value in changing apathy to interest.

Another project was to set up a hospital area in Camp I itself. Our plan was to accommodate 2,000 women who we considered would benefit by immediate hospitalisation. This necessitated emptying, delousing, cleaning and equipping about fifteen huts during the course of about fifteen days. We would reorganise a hut, and then move on to another, leaving two students in charge.

In the hut which was run by two Middlesex students and myself there were two families, consisting of two mothers, a grandmother and three children. It proved impossible to remove these people. We adopted one of the children as a mascot, christening him ‘Harpo’, for he looked exactly like the famous Marx brother. He had bright and curly hair but, unlike his namesake, a serious disposition. His main interest lay in a Bofors tractor which we used for various tasks. We in our turn were adopted by some Canadian airmen, who brought us cigarettes, chocolates, flowers and many useful domestic articles. One day they even turned up with two deer which they had shot in the nearby forest.

Under these infinitely better conditions we became more ambitious in our treatment of patients, who now enjoyed the unbelievable luxury of a narrow bunk for each person. Our main problems were starvation and diarrhoea, for by now typhus was on the wane, as most of our patients had already contracted the disease and were now convalescent. DDT proved very effective against lice, and it was estimated by the American Typhus Commission that 95 per cent of lice were eliminated by the first delousing of the huts. We occasionally saw lice, but never on our own persons, which we protected solely by DDT.

Starvation was widespread and extreme examples were common. The intractable diarrhoea encountered was of extreme discomfort to the patient, the nurses and ourselves. The theories as to aetiology were many, ranging from avitaminoses to bacterial infections. Treatment was just as obscure. The drugs used with occasional good results were opium, Albucid, sulphapyridine, ‘Tannalbin’ (a German preparation supposedly equivalent to our sulphaguanidine), nicotinic acid, chalk, charcoal and kaolin. Various combinations were tried, and possibly opium proved the most popular, although its supply was more limited than the others. Naturally the dehydration from such prolonged diarrhoea contributed to the death rate.

Tuberculosis was another problem with which it was quite impossible to cope. On clinical grounds almost a third of the people had TB, and radiologically probably more. All we could do was attempt to segregate them from the others.

Gradually Belsen Concentration Camp was cleared. The last internees to leave were those in the hospital area. My own hut was evacuated on 19 May. On making a final tour of the supposedly empty hut I found the two families quite oblivious of the fact that they were almost the only people left. They were quite willing to remain, even though the hut was about to be burned down. They suggested they might go to Russia, so I told them I would arrange for this. I often wonder whether they ever got there.

In our new hospital conditions were better, medicine became more than a possibility and research became more organised. We learned, among other things, to appreciate the devoted attention that the RAMC orderlies gave to the patients.

Camp I was systematically destroyed. The huts were burned or dynamited to the ground, and flame-throwers seared every square yard of the area. The last hut was ceremoniously fired on 23 May. A guard of honour was provided by the 113th LAA Regiment RA who, in my opinion, were the men to whom the most honour was due in the story of Belsen. They were magnificent in every way. It was at this ceremony that the Union Jack flew over the camp for the first and last time. Thus Belsen, with all that it stood for, came to an end.

But although it has ceased to exist materially, it will never be forgotten in the minds of those who were there. We know the ideology of the people who were responsible for Belsen Camp. We must never forget their creed and we must always fight against it.

from the Barts and The London Chronicle, Autumn 2005 Volume 7, issue 2

The first moments of going into camp 1 to find the incredible overcrowding of the huts. The spectacle of emaciated, dead and dying. The dead, unknown, unshriven and unmourned, being thrown by the thousand into pits and covered by bulldozers. The bodies hauled there by camp guards who were worked to total exhaustion. The local people being taken through the camp to view the results of Nazi rule – they denied any knowledge of such matters but at least most appeared shocked. The large pile of watches taken from the inmates from which we were invited to choose. The nightly fusillade of shots as the viable camp inmates took revenge on the population. A trip to Hamburg in a borrowed Jeep with the detritus of war everywhere. Celebrating the end of the war with large amounts of German wine. Flying back to Croydon with souvenirs, including a Luger (later returned to the police!). Being quarantined by the Ministry of Health because we might develop typhus.

On thing that struck me was that it was never stated that we were dealing with the result of a malignant ethnic cleansing. We were ignorant of the ethnicity of the inhabitants of Belsen, other than that they were European. To us they were the victims of the Nazis, for whatever reason, not that they might be Jewish. This was never discussed or emphasised. At that time the magnitude of the Holocaust was not known, or was concealed. Belsen was not a murder camp in the mode of Auschwitz. There were no ‘showers’ that I saw. Death came more slowly, through starvation and disease rather than by Zyklon-B.

From the Barts and The London Chronicle, Spring 2005 Volume 7, issue 1

Update

Thomas Chometon Gibson died on Saturday, May 2nd, 2021 aged 99. He was born in Burnley, England on April 30th 1921.

19,980 total views