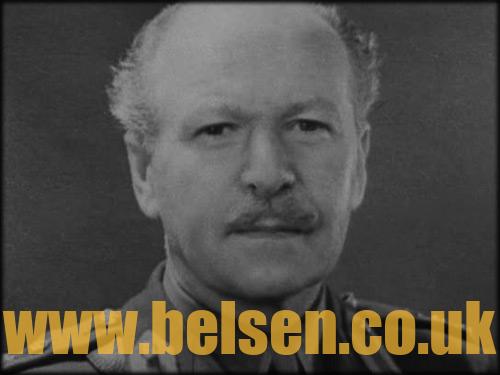

Brigadier Robert Daniell

Having smashed through Belsen’s gates and the first building he came to, scattering guards in all directions, Daniell found a trench 150 yards long filled with naked bodies; he then broke down the door of the camp hospital, in which 90 per cent of the patients were dead.

“The sight and the smell were completely appalling; they were all naked and many of them no doubt had typhus.” In the next two buildings he visited lay hundreds of skeletal people in the last stages of starvation. Hearing shots, he went to the perimeter where he found a group of would-be escapees being tortured on the wire by six Hitler Youth. He shot four of them. Daniell was sure that he never lost his self-control, but that was the nearest he came to it.

Brought up in Anglesey and schooled in Norfolk, Bob Daniell was very much a countryman:

The lure of the wild things, fur or feather, their ways and their cries remained with me all of my life. In the heat of the Indian jungles I thrilled to the cough of a leopard, and later stood like a stone as the full-bodied roar of a hungry lion resounded around me, to be answered by the wicked scream of an old bull elephant with the limitless African bush stretching out to the distant horizon.

Years later in the days of war the ability to become an unrecognisable object was to stand me in good stead. When man was hunting man, it was the first one who shot who survived.

Daniell passed out of the Royal Military Academy in 1920, second in his class, and after a period with the 1st Battery, Royal Artillery (The Blazers), during which he became an enthusiastic jockey, was posted to India, where Montgomery was his battery captain. He returned to England in 1928.

In 1929 he received his “jacket” and was posted to the 3rd Regiment Royal Horse Artillery. Then followed a period of high days and holidays during which his horse won the Grand Military Gold Cup in 1933, and he rode to victory himself in the Gunner Gold Cup at Sandown twice, in 1934 and 1938. He became Adjutant of the Westmorland and Cumberland Yeomanry before rejoining his regiment late in 1937 and leaving for Palestine.

Action started in January 1940 with the battle of Sidi Barrani under Wavell, which resulted in the surrender of some 35,000 Italian troops; Daniell was with M Battery, 3rd Royal Horse Artillery. Not long afterwards he became second in command of the South Notts Hussars. In March 1941 they broke through German lines to enter Tobruk, and for 10 months endured the siege.

They returned to Cairo to refit. But in April 1942 the 22nd Armoured Brigade was no match for Rommel’s Panzer Regiments – now equipped with new Mark VI tanks – when they advanced again from the west.

With the last of the Churchill tanks in flames, Daniell faced four Mark VI tanks coming straight for his guns. One suffered a direct hit and exploded, while the others opened up with heavy machine-guns which pierced the 25- pounder gun shields like paper, killing many of the South Notts men. The regimental padre, with four bullets in him, escaped with six wounded, while Daniell and three fellows lay as if dead. To their relief the tanks passed them by.

Early in June 1942, after collecting what was left of his men and guns, Daniell was ordered forward from the Gazala Bir Hachem minefield, to put up a barrage in a futile attempt to discourage German movement northwards. Dawn broke as the regiment was topping a rise and they were met by a hail of shells. Caught on a stony ridge, they became surrounded by German tanks. Casualties were heavy. Daniell and his men could not move, and their orders were precise: stand and fight where they were to the last man and the last round.

For two days the situation deteriorated. Having collapsed with fatigue Daniell awoke to find a German staff car beside him with two generals in it. He leapt on to the running board but was dislodged when the staff officer hit him over the eye with his map case. All the vehicles were burning as he walked over to the remaining gun that seemed intact. As a Mark VI appeared out of the smoke a gunner loaded the 25-pounder for him and he fired at point-blank range. The tank was destroyed but Daniell had been seen and machine-gun fire was heavy. Daniell rolled into the smoke of a burning vehicle as German infantry overran the position. In an hour it would be dark, and the noise of battle subsided. Untouched, Daniell climbed into to his 8cwt truck, still miraculously serviceable, evaded four Mark VI tanks and headed south for the open desert. The wheels were blown away by an 88mm machine gun, and a German sergeant shouted to him to join his post. Daniell walked off into the dark with his water bottle and the sergeant didn’t open fire. Several days later, in very poor shape, he was picked up, the sole survivor of the Battle of the Cauldron, by Gerald Grosvenor, a friend, in his tank.

After the battle of El Alamein Montgomery offered him the command of 3rd RHA. Roscoe Harvey also came up with his 4th Light Armoured Brigade, and Daniell remained with him until they reached the Baltic at Lubeck two years later. The pursuit of Rommel was to continue until May 1943 when Tunis was relieved and the North Africa Campaign was over. It was during that campaign that Daniell won his first DSO.

On his return to England in July 1943 he was given command of the 13th HAC, RHA. There was little time to prepare for the invasion of which they were so soon to be a part.

Only the toughest of fights enabled the 11th Armoured Division, commanded by Harvey, to break out from the Normandy beach-head. Operation Goodwood got three armoured divisions across the Orme near Caen and Quatre Bras was taken in spite of heavy casualties. There was savage fighting close to Paris; then they swept on to Amiens and Brussels and eventually Antwerp, averaging 53 miles a day. The advance into Holland, and on to Arnhem, was slower with lines of communication stretched to the limit.

It was on 19 April 1945 that Daniell passed a group of buildings, some railway wagons, and an archway of laurels guarded by Romanians. Having earlier seen similar wagons in Normandy, when he had liberated a trainload of Jews bound for Germany, his suspicions were aroused and he asked Harvey for permission to investigate; he was given two hours. Driving his tank through the gate he discovered Belsen. It was the only concentration camp to be liberated by the British army.

Although the campaign in northern Europe was shorter than in the desert the fighting was intense and fierce; here Daniell won his second DSO.

At last the division reached Lubeck. Orders were received to proceed to Kiel, and in one of the last acts of the war Bob Daniell single-handedly captured the crew of the scuttled U-boat 141, whom he found hiding in a barn.

After the war he remained in the Army with commands in Norfolk and Kent, until he was appointed to the Sovereign’s Body Guard in 1951. He served as a Gentleman at Arms for 20 years.

Robert Bramston Thesiger Daniell, soldier: born London 15 October 1901; DSO 1943, and Bar 1944; married 1929 Betty Priestman (died 1994); died Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk 11 December 1996.

The Independent

***

He was among the first Allied soldiers to witness the horrors of the concentration camps. At Bergen-Belsen, a guard kept a dog that tore up children and patients on lower bunks in the hospital were suffocated by the excrement from patients on top.

“What I saw in those two hours changed me for the rest of my life,” Daniell told The Associated Press in a 1992 interview. “Since then, I have not had any normal feelings about any German man or woman who was alive at that time. I hate them all.”

On April 12, 1945, Daniell and his tank crew entered Bergen-Belsen, where an estimated 37,000 prisoners, mostly Jews, died of starvation, disease, beatings and torture. Anne Frank, whose diary gave the Nazi persecution of Jews a face and a name, died there a month earlier.

Daniell was a lieutenant colonel commanding the 13th Honorable Artillery Company, part of the 11th Armored Division. He was given two hours to check out the camp north of Hanover, Germany.

Walking around with a revolver, he shot the lock off one building, which turned out to be the hospital.

“It was crammed with tiers of bunks on which lay starving, sick and helpless people. Those in the bottom tiers had drowned in urine and excrement coming down from those at the top,” he said.

In some large shelters he came across hundreds of naked or nearly naked, skeletal people lying on straw. Five little children sat on the bare, bloated corpse of a woman _ playing a game of short and long straws.

“As I was trying to get the lock off a shelter, I noticed an extremely well-dressed woman with an Alsatian on a lead behind me,″ he said. “She was Irma Grese, the guard who got her dog to tear little children to pieces.”

He then heard shots: prisoners shot by guards as they tried to escape.

“There were Hitler Youth shooting prisoners so they would die in agony, the men in the groin and the women up the backside. I was so disgusted I shot the guards with the last four rounds I had,” he said.

“There was a huge trench with probably 3,000 corpses in it. Putrefying bodies give off gases which make the bodies move and the pile was heaving as if the dead were alive.”

It was three more days before British forces officially liberated the camp. At the time, 10,000 corpses lay on the ground, killed by guards as the Allies approached. Of the remaining 38,500 prisoners, barely a third lived.

Grese was among 11 staff members who were sentenced to death by a British military court and hanged in December 1945.

Daniell was born in London on Oct. 15, 1901. He attended Sandhurst, the Royal Military Academy.

He remained in the army until retirement in 1952, serving in India, the Middle East, as well as in Europe and North Africa during World War II.

Daniell took part in the Normandy invasion in June 1944 as part of the 11th Armored Division, which went from Caen into Belgium for the capture of Antwerp, into southern Holland and then north Germany.

He won the Distinguished Service Order while fighting in North Africa, and a second citation in the European campaign.

After retiring from the army, he served 20 years as one of the bodyguards of Queen Elizabeth II.

His wife, Betty, died in 1994. They had no children.

Associated Press

***

ARCHIVE COMMENT

We compile accounts ‘as is’ and rarely comment on the accuracy but this one had to be picked out.

What a load of tosh! I’m sure this man had a sparkling military career however, the accounts at Bergen Belsen concentration camp are nothing more than complete fiction. ED.

7,942 total views